Introduction

The disruptive influence of change (Kaluzny & O'Brien, 2015), political instability, deregulation of political power and opposing current realities (Gergen, 1997; Mosala, Venter & Bain, 2017) are increasingly intensifying. Growing electronic connectivity amid wide-ranging markets (Castells, 2010; Kevin, 1999), the emergence of e-business (Du Toit, 2010), the repositioning of leading current economies, and the emerging new economies (Kevin, 1999), are all rapidly increasing the tempo of change around the globe (Burke & Trahant, 2000).

Metaphorically, the above phenomenon manifests as continuously onward spiralling kinesis, mimicking an undirected, sporadic and erratic movement of a cell, an organism, or part thereof, in response to an external stimulus (Ansoff & McDonnell, 1990). However, the inverse of the onward spiralling movement is the constant regulation of an organism’s internal conditions ‒ a process described as homeostasis (Cannon, 1929). Homeostasis is an evolution of response mechanisms that balance the wellbeing and functioning of the organism or the cell, irrespective of what the external changing conditions are (Rogers, 2020). Rogers (2020) further describes homeostasis as the organism’s constant self-regulation towards a relatively stable equilibrium that is best for survival. In an instance where the homeostasis is successful, existence continues as normal, however, should the homeostasis be ineffective, existence terminates. Effective homeostasis is thus sustaining a dynamic equilibrium, wherein change is continuously occurring, though comparatively constant conditions prevail (Rogers, 2020).

Change is Constant, or Change is a Constant

Change is Constant, or Change is a Constant

The interpretation of the above raises the question of whether Change is constant, or change is a constant. Change described as constant (noun), indicates a quantity that does not vary (Manser, Feinstein, Grandison, Fergusson, McIntosh & Wren, 2001). Change described as a constant (adjective) is an indication that change is unvarying; persistent in purpose, dedication, or affection; uninterrupted in time and indefinitely ongoing (Manser et al., 2001). The choice between the two terms then depends on where the emphasis should be in the context of the application. In layman’s terms, this means that change is continuously happening, and in response to the continuous change an entity has to be mobile to adapt to the change, which brings about a different perspective within the entity; and this occurrence is ongoing (Kanter, 2011). In correspondence, Will Rogers, a well-known stage and motion picture actor of the previous century, remarked; “It isn’t enough to be on the right track; you're liable to get run over if you stay there” (Esar, 1995:423).

While change is depicted as a constant in societies, and more particularly, in business endurance, it would appear that the rate of change is accelerating (Wals & Corcoran, 2012). In the same way, it seems apparent that change creates discomfort for some and is sometimes difficult for others. Beaman (2012) notes that only some people in the workplace embrace change. However, if change is a constant, and inevitable, the question is whether people can experience change as an ongoing affair, as if it were the norm, almost as an evolution of some sorts, and thus can experience change as positive. These questions are amongst a few that will be answered in the course of the subsequent Blogs. Nonetheless, before answering these questions, certain elements require clarification, such as the distinction between change and change management, the linearity of change and change and transformation.

Change and Change Management

Change and Change Management

Change definitions have many variations. The literature indicates that definitions of change depend on the context in which change is explained (Hodgson, 2006).

Hodgson (2006) makes a distinction between changes as institutional, organisational, team and individual phenomena. Change then modifies an entity’s or an individual’s environmental, situational, physical or mental condition, which results in circumstances that challenge existing paradigms (Quattrone & Hopper, 2001), transforming the entity or individual within (Manu, 2017). Given this distinction, and because of change being a reciprocal continuous occurrence, two further questions become apparent: is change both a cognitive phenomenon and a universal occurrence, and is change a linear progression, or a systemic evolution (Quattrone & Hopper, 2001)? Additionally, Quattrone and Hopper (2005), reason that change is not a linear process and that it calls for a renewed definition to describe change. Yet, most change management processes transpire along a linear path (Better Business Learning Pty Ltd, 2017). Quattrone and Hopper (2005) argue that an enriched perspective on change would revitalise change efforts and that effective change efforts depend on well-executed change management practices (Kotter & Cohen, 2002).

Some define change management, in contrast to change, as the systematic approach to dealing with change both from the point of view of an individual and an organisation (Javidi, 2003). Javidi (2003), indicates that deliberating on change management can be a bewildering semantic excursion, since change management can be thought of as a process (Kotter, 1995), a system (Senge & Sterman, 1990), a business speciality (Thomas, 2010), and a body of knowledge (Smith, King, Sidhu & Skelsey, 2014) that transform the current condition of an entity or an individual entirely (Manu, 2017).

Linear Change versus Change as a Systemic Evolution

Linear Change versus Change as a Systemic Evolution

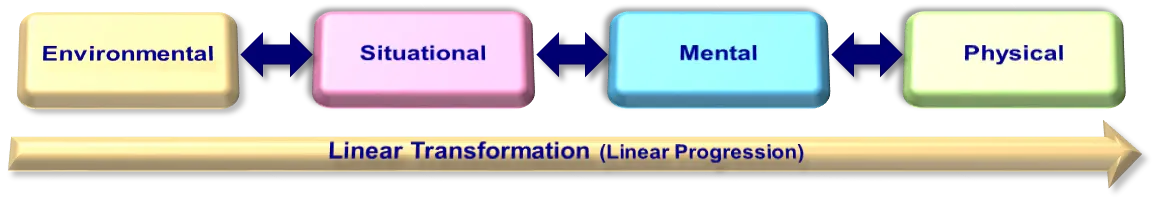

Figure 11 and Figure 12 are suitable for illustrative purposes only, of how the author interprets the difference between change as a linear progression, opposed to change being a systemic evolution, based on the four elements described by Quattrone and Hopper (2001) above. Figure 11 provides an illustration of the author’s interpretation of the linear transformation process, depicting Quattrone and Hopper’s (2001) four elements.

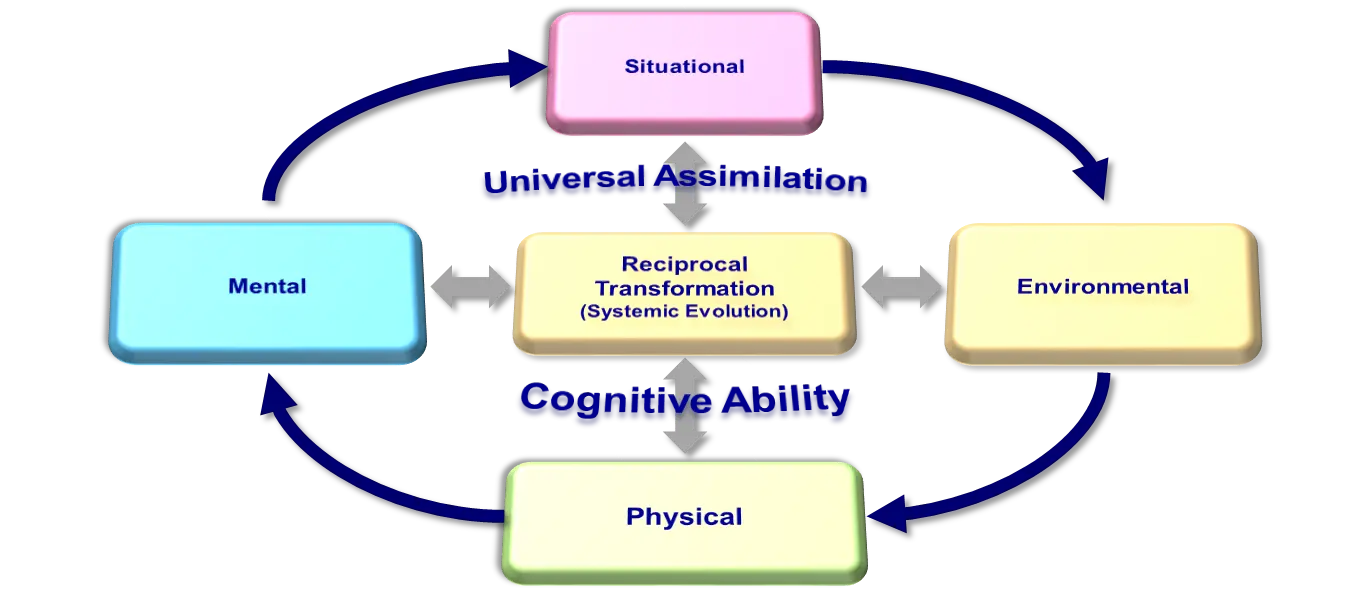

Figure 12 acts as an illustration of the author’s interpretation of the reciprocal transformation process, depicting the four elements described by Quattrone and Hopper (2001). Quattrone and Hopper (2001), indicate that the four elements that result in circumstances that challenge existing paradigms are because of the cognitive ability and the universal assimilation of the individual.

Furthermore, change management in organisational development and business management arenas has been a perpetual and fashionable topic over the last three decades (Nadler & Tushman, 1997), which is continuing (Kotter, 2011). The organisation’s need for sustainability repeatedly focused on continuous performance or quality improvement and organisational learning, implicating change as constant and necessary for organisational success, which brings about change that progresses through defined occurrences (Sushil, 2013).

The organisation’s need for continuous improvement and sustainability is in constant conflict with the individual’s conduct in answering to these needs (Hodgson, 2006). Although continuous improvement occurs gradually and aims to make small incremental changes over time (Savolainen & Haikonen, 2007), change itself is not necessarily an improvement, however, to improve requires a change (Yudkowsky, 2015), and in some instances transformation (Du Toit, 2020).

Change and Transformation

Change and Transformation

Differentiating between the concepts of change and transformation is also important. Manu (2017) suggests that during change new probable outcomes come about, whilst engaging in transformation, new possibilities materialise as a result, which is significant as some of these are unintended outcomes to both the entity and the individual. In contrast, Gottfried (2004) indicates that change to the alter ego is not possible; however, when transformation occurs, the viewpoint of the individual changes dramatically. In this instance, transformation is an observable new reality, whereas change is the motion of getting there. The individual thus experiences change as a personal endeavour (Kanter, 2011). The author theorises that when change is constant and evolutionary, the individual transforms because the change is internal to the individual.

Therefore, transformation is about modifying understandings so that an individual’s everyday behaviours accomplish the anticipated results (Kenworthey & Nadler, 2014). Kenworthey and Nadler (2014) indicate that change happens in individuals first, and only then in organisations.

In the event where change is viewed as responsive and a constant, the change obligation is driven externally from the individual, and the individual adjusts as long as the perceived pressure to change is upheld (Burke & Litwin, 1992). In this instance, change is about using external influences to modify behaviour, to achieve anticipated results. Although neither concept appears to be more appropriate than the other, the peculiarity is important in the context of this discussion and in this regard, the author proposes the following point of departure as an initial assumption of these concepts:

Change is evolutionary, ongoing, personal and transformational.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The concept that change is evolutionary, ongoing, personal and transformational, acts as clarification of the relevance of the terms transformatology and continuous change that will be the focus of future Blogs.

In this context then, change and change management are approached as an integrated and reciprocal occurrence (Wiens & Moss, 2005), being the inclination of people in response to a changing environment vis-à-vis changing people to adapt to a change in the environment.

This dilemma provides the foundation for the background to the Insights to follow.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Ansoff, I. H. & McDonnell, E., 1990. Implanting Strategic Management. 2nd ed. Cambridge UK: Prentice Hall.

Better Business Learning Pty Ltd, 2017. Change Activation. [Online] Available at: https://changeactivation.com/change-management-models/ [Accessed 25 11 2017].

Burke, W. W. & Litwin, G. H., 1992. A causal model of organizational performance and change. Journal of Management, 18(3), pp. 523-545.

Burke, W. W. & Trahant, W., 2000. Business Climate Shifts: Profiles of Change Makers. Boston, MA: Butterworth Heinemann.

Cannon, W. B., 1929. Organization for Physiological Homeostasis. Psychological Reviews, 9(3), pp. 399-431.

Du Toit, P. J., 2010. An Alternative Approach to “Best Fit” Integrated e-Business Management Facilities and –Solutions for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). 3rd ed. MBL. Midrand: UNISA.

Du Toit, P. J., 2020. Transformatology: The Art and Science of Enhancing Continuous Change. 1st ed. Doctor in the Management of Technology and Innovation. Modderfontein: The Da Vinci Institute for Technology Management.

Hodgson, G. M., 2006. What Are Institutions?. Journal of Economic Issues, 40(1), pp. 1-25. Javidi, M., 2003. Collaborative Change Management. Intercultural Communication Studies, XII(2), pp. 1-12.

Kaluzny, A. D. & O'Brien, D. M., 2015. Managing Disruptive Change in Healthcare: Lessons from a Public-Private Partnership to Advance Cancer Care and Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kanter, R. M., 2011. The Change Wheel: Elements of Systemic Change and How to Get Change Rolling. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kenworthey, B. & Nadler, J., 2014. Law, Moral Attitudes and Behavioral Change. In: E. Zamir & D. Teichman, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Behavioral Economics and the Law. Oxford: Oxford Academic Publishers, pp. 241-267.

Kevin, K., 1999. New Rules for the New Economy: 10 Radical Strategies for a Connected World. New York: Penguin Books.

Kotter, J. P., 1995. Leading Change: Why Transformational Efforts Fail. Harvard Business Review, 73(2), pp. 59-67.

Kotter, J. P., 2011. Forbes. [Online] Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkotter/2011/07/12/change-management-vs-change-leadership-whats-the-difference/#2d59ddf64cc6 [Accessed 28 08 2020].

Kotter, J. P. & Cohen, D. S., 2002. The Heart of Change: Real-life Stories of how People Change Their Organizations. 1st ed. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Manu, A., 2017. Transforming Organisations for the Subscription Economy: Starting from scratch. 1st ed. New York: Routledge.

Nadler, D. A. & Tushman, M. L., 1997. Competing by Design: The Power of Organizational Architecture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Quattrone, P. & Hopper, T., 2001. What does Organizational Change Mean? Speculations on a Taken for Granted Category. Management Accounting Research, Volume 12, p. 403–435.

Rogers, K., 2020. Homeostasis. In: Encyclopaedia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

Savolainen, T. & Haikonen, A., 2007. Dynamics of organizational learning and continuous improvement in six sigma implementation. The TQM Magazine, 19(1), pp. 6-17.

Senge, P. M. & Sterman, J. D., 1990. Systems Thinking and Organizational Learning: Acting Locally and Thinking Globally in the Organization of the Future. Cambridge, Sloan School of Management: MIT.

Sushil, 2013. Does Continuous Change Imply Continuity. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 14(3), pp. 123-124.

Thomas, J. C., 2010. Speciality Competencies in Organizational and Business Consulting Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wals, A. E. J. & Corcoran, P. B., 2012. Learning for Sustainability in Times of Accelerating Change. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Wiens, J. A. & Moss, M. R., 2005. Issues and Perspectives in Landscape Ecology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yudkowsky, E., 2015. Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality. California: hpmor.com & fanfiction.net.